Obtaining the accounting, however, is only half the battle. After receiving the accounting, the beneficiary must determine whether the accounting is complete and accurate and whether the fiduciary has acted improperly. Even more difficult, however, can be quantifying the damages caused trustee’s or executor’s improper behavior.

The purpose of this article is to provide an action plan for the disgruntled trust or estate beneficiary to analyze an accounting produced by a fiduciary.9 The article discusses the statutory requirements for trust and estate accountings and summarizes the process of requesting, obtaining, and organizing the documents used to create the accounting. Then, the article explains common components of a fiduciary accounting, to assist the beneficiary in starting his or her review of the accounting and the supporting documentation. The article identifies certain key questions within each component that must be answered. Finally, the article identifies the most common forensic accounting method employed to answer these key questions. Common issues which are frequently encountered are also noted. This strategic process can allow a beneficiary to quickly identify issues with the accounting and thereby ascertaining the viability of legal claims against the fiduciary, the amount of potential damages, as well as the beneficiary’s chances of obtaining interim relief, such as enjoining or removing the trustee or executor.

A. Step 1 – Determine if the Accounting Meets the Requirements of the Texas Trust Code or Texas Estates Code

This article assumes the beneficiary has made a proper and timely demand for a statutory trust or estate accounting and that the trustee or executor is legally obligated to produce the accounting.10 Once the trustee or executor produces the accounting in response a formal demand, the first step is to determine whether the accounting includes all the information required by statute.

With respect to a trust accounting, Texas Trust Code Section 113.152 requires the accounting to show.

- all trust property that has come to the trustee’s knowledge or into the trustee’s possession and that has not been previously listed or inventoried as property of the trust;

- a complete account of receipts, disbursements, and other transactions regarding the trust property for the period covered by the account, including their source and nature, with receipts of principal and income shown separately;

- a listing of all property being administered, with an adequate description of each asset;

- the cash balance on hand and the name and location of the depository where the balance is kept; and

- all known liabilities owed by the

With respect to an estate accounting, Texas Estates Code Section 404.001 requires an executor to furnish the person making the accounting demand with an exhibit in writing, sworn and subscribed by the executor, setting forth in detail:

- the property belonging to the estate that has come into the executor’s possession as executor;

- the disposition that has been made of the property described by Subdivision (1);

- the debts that have been paid;

- the debts and expenses, if any, still owing by the estate;

- the property of the estate, if any, still remaining in the executor’s possession;

- other facts as may be necessary to a full and definite understanding of the exact condition of the estate; and

- the facts, if any, that show why the administration should not be closed and the estate

In many instances, the accounting will fail to include all the information required by law. Identifying any deficiencies with respect to these basic statutory requirements is crucial.

B. Step 2 – Obtain the Documents Used to Create the Accounting

Not all accountings are created equal. Unfortunately, the “accounting” a fiduciary provides may merely consist of a summary of activity or a series of ledger entries. Rarely will the accounting include supporting documents, but without them, the beneficiary has no meaningful way to verify the completeness and accuracy of the accounting.

The beneficiary should always request the documents used to create the accounting. The timing and content of the fiduciary’s response can serve as a good indicator as to whether the fiduciary has adequately kept and maintained records.11 At a minimum, the beneficiary should request those documents used to support the accounting’s core components, namely the accounting’s reporting of:

- assets;

- liabilities;

- income/deposits;

- expenditures;

- cash reconciliation;

- changes in property; and

- fiduciary

The following categories of documents for each accounting component are particularly useful in making a request for documents:

(1). Assets

- Documents describing, discussing, or mentioning the title of assets under administration, including deeds, titles, assignments, account agreements, life insurance and annuity policies, corporate formation documents, contracts, purchase and sale agreements, partnership agreements, tax notices, tax appraisals,

- Documents directly describing, discussing, or mentioning assets under administration at a particular point in time, including deeds, titles, assignments, asset inventories, personal financial statements, or business financial statements (such as income statements, balance sheets cash flow statements or similar types of documents).

- Documents indirectly describing, discussing, or mentioning assets that may be or were under administration at a particular point in time, including tax returns, tax assessments, correspondence, wills/trusts and associated memoranda, desk files, notes, management agreements, retention contracts with professional advisors, records of safe deposit boxes (e.g. bank charges for such) among other

- Other documents describing, discussing, or mentioning claims due and owing to the trust and/or

(2). Liabilities

- Documents describing, discussing, or mentioning debts owed by the trust or estate at particular points in time, including vendor invoices and statements, correspondence with vendors, loan and line of credit documents, mortgage paperwork, correspondence with creditors, property tax notices, tax returns, and credit card statements.

- Documents describing, discussing, or mentioning monthly or other periodic budgets or listings of monthly or other periodic expenses compiled for or by the trust or the estate (or the decedent), including checkbooks, bank statements showing electronic debits, ATM

withdrawals and checks cleared, estimated tax payments, and bank reconciliations.

(3). Income/Deposits

- Documents describing, discussing, or mentioning income of the trust or estate, including financial account statements, income statements, tax returns (with supporting documents and workpapers), and income reporting forms (e.g., 1099-INT, etc.).

- Documents describing, discussing, or mentioning deposits of the trust or estate, including financial account statements, brokerage account statements, certificates of deposit, Individual Retirement Account statements, 401(k) plan statements, pensions, annuities and other account statements, as well as documentary evidence of activity, including deposit slips, copies of deposited checks, and wire

(4). Expenditures

- Documents describing, discussing, or mentioning expenditures of trust or estate assets, including financial account statements, withdrawal slips, inter-bank transfers, cancelled checks, check registers, expense reports with supporting documentation, account reconciliations, receipts, and

- Documents describing, discussing, or mentioning invoices and receipts supporting expenditures of the trust or estate

(5). Changes in Property

- Documents describing, discussing, or mentioning any transfer or sale of:

- any interest in any real property of the trust or estate, including assignments, contracts, deeds, deeds of trust, agreements, or closing statements;

- any personal property of the trust or estate, including assignments, bills of sale, contracts, and/or titles; or

- any financial assets of the trust or estate, such as stocks, bonds, mutual funds, or other business investments.

- Documents describing, discussing, or mentioning the transferee, the nature of the transfer (i.e., whether it was a gift or it was for consideration), the reasons for the transfer, and the terms of the

- Documents describing, discussing, or mentioning the disposition of the proceeds of such sales including documents that describe, discuss, or mention the buyer, the gain or loss recorded, and the terms of

(6). Fiduciary Compensation

- Documents describing, discussing, or mentioning fiduciary compensation, including worksheets or statements showing the method for calculating such compensation and showing the fiduciary services performed and the hourly rate charged for such

C. Step 3 – Inventory the Documents Obtained

If and when the fiduciary provides the supporting documents used to create the accounting, the beneficiary should inventory the documents. Inventorying the supporting documentation has several important uses, such as:

- identifying holes in the accounting, including unaccounted-for assets and liabilities and expenditures, sales, and transfers with no supporting documentation;

- facilitating efficient additional follow-up requests for information;

- revealing instances where assets are not properly titled in the name of the trust or estate; and

- establishing potential breaches of the trustee’s or executor’s duty to keep and maintain records.

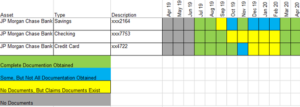

In this regard, using a chart in excel can be incredibly useful. For example, assets can be listed down the “y” axis with the time period (e.g., month and year) charted along the “x” axis. A color scheme or codes may be utilized to show those categories of assets/liabilities for which the fiduciary has provided documentation as well as the status of documentation generally:

As the beneficiary obtains new documents, the chart can be updated with new worksheets at different time intervals. This kind of visual aid can be incredibly useful and persuasive in a court setting.

D. Step 4 – Answer Key Questions and Utilize Commonly Employed Forensic Accounting Methods to Identify Potential Problems

Once the beneficiary receives the accounting and as much of the supporting documentation and related disclosures that are reasonably available, the beneficiary should then analyze the information with the primary goal of answering the million-dollar question:

Is the accounting complete and accurate?

In reviewing the accounting and supporting documentation to attempt to answer this question, having a plan — and methodically implementing it — is critical. Perhaps the most efficient review plan is one that covers each core component of the accounting. The most common and general components to a trust or estate accounting include the thorough reporting of:

- assets;

- liabilities;

- income/deposits;

- expenditures;

- cash reconciliation;

- changes in property; and

- fiduciary

Each accounting component will include its own common issues, key questions associated with each issue, and forensic accounting methods frequently employed to answer them. When it comes to these techniques, a “one-size fits all” approach does not exist. Each factual situation presents unique issues and challenges. Therefore, it may be necessary to consider a variation on these commonly employed forensic accounting methods and/or utilizing other procedures as the facts and circumstances warrant.

For ease of reference, these components, common issues, key questions, and forensic accounting methods are illustrated and explained through a sample checklist.

(1). Assets

The assets reported on an accounting refer to the resources of economic value which are owned by the trust or estate. The assets can consist of real property, as well as tangible and intangible personal property. Claims due and owing to the trust or estate, such as promissory notes payable to the trust or estate and/or other rights to income, are also considered assets. Depending on the context, the assets may be characterized as separate or community property.

(2). Liabilities

The liabilities reported on an accounting refer to the debts owed (or in some cases, expected to be owed in the future) by the trust or estate. For example, in the context of a trust, mortgages on real property owned by the trust, as well as loans owed by the trust, would be considered liabilities. In the context of a decedent’s estate, the unpaid creditors of the decedent are typically listed as liabilities owed by the estate. Some common examples of debts to be owed in the future might include anticipated tax liabilities or expenses of administration, including fiduciary compensation and professional fees.

(3). Expenditures

The expenditures reported on an accounting usually refer to the expenses and disbursements made from the trust or estate. An expense is commonly understood as a cost the trust or estate incurs to either produce revenue or which are necessary to administer the trust or estate. An expenditure may refer to either the payment of an expense or the disbursement of an asset (for example, a distribution). Transfers from one account to another are also commonly reported under the category of expenditures.

Estate and trust expenses can present a field day for an opportunistic fiduciary. A beneficiary must examine reported expenses closely to determine and verify whether they are reasonable and/or whether they benefited the trust or estate or, alternatively, whether the expenses benefited the fiduciary personally. Texas law places the burden on the fiduciary to account for expenditures.34

In addition to the key questions and methods referenced above, it is worth noting that a fiduciary may mix trust or estate funds with their own funds, thereby engaging in commingling. In such circumstances, the trustee or executor will have the burden to trace and establish what portion is the trustee’s or executor’s and what portion belongs to the trust or estate.39 In fact, if a trustee or executor commingles funds, “the beneficiary may follow the trust [or estate] property, and claim every part of the blended property which the trustee [or executor] cannot identify as his own; that if he fails to keep clear, distinct and accurate accounts, all presumptions are against him, and all obscurities and doubts are to be taken adversely to him.”40 If the trustee or executor has kept and maintained adequate records, the records should be used to determine amounts owed to the trustee or executor, personally, and the trust or the estate.

(4). Cash Reconciliation

Cash reconciliation refers to the process of matching the balances reported in the accounting for the cash accounts for an estate or trust with the corresponding information on a bank statement. The main goal of this exercise to determine whether there any differences between the balances reported on the accounting and on the financial statements – if there is, the account does not balance. The steps to reconcile a cash include taking the balance at the beginning of the period, adding the inflows for the period, subtracting the outflows for the period, and comparing the corresponding ending balance at the end of the period with the balanced reported on the financial statement. There are many reasons why an account may not balance, but the most common reasons include math errors, outstanding checks which have not cleared, not including bank fees, or fraud (for example, where the accounting reports cash deposited in a certain amount, but a lesser amount was actually deposited, resulting in someone pocketing the difference).

(5). Changes in Property Reported

Changes that occur to trust or estate property in an accounting generally fall into three categories: (1) the disappearance of an estate asset (due to sale, liquidation, transfer, exhaustion or otherwise); (2) the combination or division of an asset, such as accounts or trusts; and (3) changes in market value for investment accounts.

(6). Fiduciary Compensation

Fiduciary compensation refers to the fee a trustee or executor may be entitled to take for serving. While an in-depth treatment of fiduciary compensation is beyond the scope of this article, suffice it to say that fiduciary compensation can present numerous traps. Before examining the compensation set forth in an accounting, a fiduciary must closely review the terms of the trust, will, or other document governing compensation; of if the trust or will is silent as to compensation, then to the terms of the Estates Code or Trust Code.44 When analyzing the fiduciary compensation reported on the accounting, the beneficiary’s main goals are to confirm that compensation is commensurate with the terms of the governing document and/or law and are otherwise reasonable in the circumstances.

E. Conclusion

Properly analyzing trust and estate accountings will often require the assistance of trained professionals, such as a forensic accountant, as will the forensic accounting processes described above. This forensic analysis is also often performed under the supervision of legal counsel experienced in trust or estate matters with the protections and benefits of the attorney-client privilege and attorney work product privilege. The beneficiary may want to engage the services of a private investigator trained in financial issues if significant public-records research is required. For significant privately held business interests, it may be necessary to have the business interest valued by an experienced professional independent from the trust or estate, such as one recognized as a Certified Valuation Analyst (CVA), one recognized as Accredited in Business Valuation by the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (ABV), or a professional otherwise qualified by appropriate professional training and experience. Similarly, a qualified real estate appraiser or consultant may be of assistance in examining property transfers and valuation. Moreover, in cases of potential fraud, engaging experienced legal counsel and experts trained in analyzing, identifying, and quantifying losses due to such embezzlement and/or mismanagement can be crucial to a successful recovery.

Verifying the completeness and accuracy of a trust or estate accounting is vitally important to protect the beneficiary’s rights. Properly analyzing these accountings, however, can be challenging – particularly where the trustee or executor intentionally or unintentionally presents challenges to the beneficiary. Whenever possible, a trust or estate beneficiary should use experienced legal counsel and forensic accountants to double check the fiduciary’s work product and identify problem areas. Understanding the legal significance of the problem areas — that is, whether the trustee or executor’s acts and/or omissions were improper under the governing instrument and applicable law — arms the beneficiary with knowledge, and knowledge is power.

1 © 2021 Mark R. Caldwell, Bryan Finley, & J. Ellen Bennett. All rights reserved. This article should not be considered as, or as a substitute for, legal advice, and it is not intended to, nor does it create, any attorney client relationship. Since the information herein is general in nature, it may not apply to an individual or specific factual circumstance. Therefore, the decision to take (or not take) legal action should not be based upon the information contained herein.

2 Mark R. Caldwell, Licensed Attorney (Texas), is a shareholder at the law firm Caldwell, Bennett, Thomas, Toraason & Mead, PLLC. Mr. Caldwell dedicates this article to Melanie Baloga, former court auditor of Dallas County Probate Court No. 3 and Dallas County Probate Court No. 2, for her steadfast and generous mentorship in the area of fiduciary accountings.

3 Bryan A. Finley, Certified Public Accountant (Texas) and Certified Fraud Examiner, is a Director with Ryan Fraud and Forensic Recovery LLC.

4 J. Ellen Bennett, Licensed Attorney (Texas), is a shareholder at the law firm Caldwell, Bennett, Thomas, Toraason & Mead, PLLC.

5 In certain circumstances, depending on the terms of the trust and the type of beneficiary, a trust beneficiary may request a formal accounting – or “written statement of accounts” – of the trust. See Tex. Trust Code §

113.151. This written statement of accounts must conform with the requirements set out in TTC § 113.152. See also American College of Trust and Estate Counsel National Fiduciary Accounting Standards, May 1984 and as amended.

6 At any time after the expiration of 15 months after the date the letters testamentary or letters of administration are issued, an interested person, as that term is defined in Texas Estates Code Section 22.018, may request an accounting of an estate. Tex. Estates Code § 404.001.

7 If the accounting is not delivered on or before the 90th day after the trustee receives the demand, the beneficiary may file suit to compel the trustee to deliver the accounting. Tex. Trust Code § 113.151(a).

8 Texas law provides that if the accounting is not delivered on or before the 60th day after the executor’s receipt of the demand, the person requesting the accounting may file suit to compel delivery of the accounting. Tex. Estates Code § 404.001.

9 While this article explains the methodology to analyze a fiduciary’s accounting, the article does not intend to explain the legal significance of every type of act, omission or transaction reported – in other words, whether such act, omission, or transaction gives rise to liability for the fiduciary.

10 For example, with respect to a trust, the trust does not eliminate or otherwise restrict the beneficiary’s right to an accounting.

11 Texas case law definitively holds that a trustee is required to keep full, accurate, and orderly records concerning the status of the trust estate and of all acts performed thereunder. Beaty v. Bales, 677 S.W.2d 750, 754 (Tex. App.—San Antonio 1984, writ ref’d n.r.e.), citing Shannon v. Frost National Bank, 533 S.W.2d 389 (Tex. Civ. App.—San Antonio 1975, writ ref’d n.r.e.). Similarly, the personal representative is required to keep adequate records. Walling v. Hubbard, 389 S.W.2d 581, 589 (Tex. Civ. App.–Houston 1965), writ dismissed w.o.j. (Nov. 3, 1965), writ refused N.R.E (Nov. 3, 1965)(“It is the duty of an executor to maintain books of account showing all income of the estate being administered, as well as all items of expense paid out on behalf of the estate.”). Any breach of duty and mismanagement of the estate by an independent executor renders the independent executor individually liable. Ertel v. O’Brien, 852 S.W.2d 17, 21 (Tex. App.—Waco 1993, writ denied)(citing Drake v. Trinity Universal Ins. Co. 600 S.W.2d 768, 772 (Tex. 1980); Rice v. Gregory 780 S.W.2d 384, 388 (Tex. App.—Texarkana 1989); Interfirst Bank–Houston v. Quintana Petroleum, 699 S.W.2d 864, 874 (Tex. App.—Houston [1st Dist.] 1985))).

12 With respect to Estate accountings, common issues include inconsistencies between the assets reported in the Decedent’s estate inventory, appraise and list of claims with the assets reported in the accounting.

13 When a trust or estate is entitled to receive an asset, but the asset is not yet in the trustee’s or executor’s possession, then the right to the asset should be reported on the accounting as a “claim due and owing” to the trust or estate. Claims due and owing to a trust and/or estate are frequently omitted in accountings. An example of a common such claim due and owing is when a trust is entitled to receive assets from the estate of a settlor upon such settlor’s death. Another example is when a decedent’s estate has a claim for one-half of community property that is under the management and control of the surviving spouse.

14 With respect to non-probate assets, the beneficiary cannot simply take the trustee or executor’s word for it that a particular account does not belong to the trust and/or estate. It is reasonable for a beneficiary to take the position that an asset is owned by the trust and/or estate until the actual beneficiary designation form confirms the contrary. Technical and fatal deficiencies in the form of a beneficiary designation may cause the designation to be invalid and require thorough analysis. See e.g. Hare v. Longstreet, 531 S.W. 3rd 922 (Tex. App.— Tyler 2017)(signature card failed to comply with the Texas Estates Code Section 113.151(b)).

15 With respect to investment-grade assets, an initial assessment is important to determine the extent to which the trust holds investments in publicly held securities or private, non-traded business interests. The value of publicly traded interest prices can be readily determined based on market quotations.

16 Often, trusts hold interests in privately held entities. If so, it is important to determine how the trustee has elected to represent the values of those assets in the accounting.

17 Real property is often reported at its tax value, which may not be the same as its fair market value (appraisals may have been used or may be necessary).

18 For tangible personal property of high value, it is important to determine if the trustee or executor used an appraisal to arrive at the value for such items.

19 A common example of an asset with uncertain value is a percentage interest in a family-controlled business. It is possible that the asset has been recorded at a historic cost of acquisition or “book value” prior to formation of the trust. If the property is said to be based on a “valuation,”, it is important to determine whether a non-independent or third-party valuation of the business interest been performed, and if so, using what methods, if any, and with what supporting workpapers and supporting documentation.

20 There are related tax consequences to valuations based on whether the asset basis has been “stepped up”properly, which are outside the scope of this article.

21 It is important to track what has happened to the assets reported, for example where numerous financial accounts have been consolidated into one or only a few accounts. Tracking the transfer of assets between multiple trusts under the management of a trustee (for example, for various individual family members) is also important.

22 Frequently encountered issues with respect to verifying the completeness of the liabilities reported include, but are not limited to, instances where the fiduciary has: (1) failed to disclose obligations (such as liabilities, contractual obligations, claims or contingent liabilities) or liabilities; (2) entered into new and otherwise unknown obligations. In that case, it is important to attempt to trace the destination of cash proceeds to accurately identify the liability.

23 Frequently encountered issues with respect to verifying that the liabilities report are valid include, but are not limited to, instances where the fiduciary has: (1) made personal expenditures on credit cards paid for with trust or estate assets; and/or (2) made expenditures which were claimed to have been allegedly for the benefit of the trust or estate, but which actually benefited the fiduciary personally, and/or, and/or the improper reimbursement for such items.

24 In the context of an estate accounting, the surviving spouse may be liable for certain expenses. See e.g., Featherston and Pargaman, Death of a Spouse: Phantom Estate Administration¸ State Bar of Texas, 43d Annual Advanced Estate Planning & Probate (2019) Section IV.

25 Frequently encountered issues with respect to income completeness often occur in situations in which the documents supporting the trust and/or estate’s right to income are missing, incomplete, or altered. In those situations, a fiduciary can fail to report income or under-report income. Unless the beneficiary asks for, receives, and analyzes the underlying documents supporting the right to income, the situation is ripe for an unscrupulous fiduciary to under-report income and pocket the difference between the amount reported and the amount received under the agreement/contract. This dynamic can be present in a variety of factual circumstances, including instances where the trust or estate owns real property which is be leased to tenants who pay in cash.

26 For example, in an estate accounting, where a surviving spouse has separate property producing income, the estate may have a claim to one-half of such income, absent an agreement between the spouses to the contrary.

27 Commingling can occur where income is siphoned off of or diverted away from the trust or estate and deposited into the fiduciary’s personal accounts.

28 Income classification and allocation methodologies, in general, follow the terms of the applicable trust or will, and in the absence of treatment, will normally follow applicable state law, which may be based on the Uniform Fiduciary Principal and Income Act (UFPIA) or earlier iterations often referred to as Uniform Principal and Income Act (UPIA) (not to be confused with Uniform Prudent Investor Act). Common issues in verifying proper income classification and allocation include instances where there are two or more beneficiaries (regardless of whether their interests are concurrent or successive), and the fiduciary misclassified or misallocated income. A fiduciary can misclassify or misallocate income to manipulate the amount of distributable net income. The latter situation often occurs when a conflict of interest exists between those beneficiaries entitled to income and those who would receive principal on the termination of a trust, death, or other triggering event. In this context, the fiduciary must especially consider his or her duty of impartiality.

29 For example, how a dividend is received affects its characterization as income or principal. Ordinary dividends are paid regularly to shareholders and are received as income, but liquidating dividends are paid upon the dissolution of an entity, distribution of a capital gain, or the return of capital and are received as principal. Other issues may include the identification of unreported capital gains and losses, the proper allocation of income and/or principal, and contributions or transfers of assets into or out of the trust or estate.

30 Generally, a trustee’s or executor’s duties with respect to investing trust and/or estate assets are governed by the terms of the trust or will. Verifying and determining the nature of and performance of investments requires analyzing the fiduciary’s decision-making process in determining the nature, risk, and performance of investments against complex legal considerations. Issues to consider in analyzing the fiduciary’s conduct are whether the fiduciary: (1) is being compensated, directly or indirectly, from the trust or other instrument or by use of the various techniques addressed in this article; (2) is subject to duties or standards in the Uniform Prudent Investment Act that have been expanded, restricted, eliminated, or otherwise altered by the provisions of the trust; (3) reviewed the trust assets and made and implemented decisions concerning the retention and disposition of assets, the trustee, within a reasonable time after accepting the trusteeship or receiving trust assets, to bring the trust portfolio into compliance with the purposes, terms, distribution requirements, and other circumstances of the trust, and with the requirements of Texas Trust Code, Chapter 117. See Tex. Trust. Code 117.006; (4) acted in reasonable reliance on the provisions of the trust and making investment decisions;

(5) made investment decisions consistent with the standard of care outlined in Texas Trust Code Section 117.004; (6) properly delegated investment decisions and properly supervised investment agents; (7) may have a conflict of interest in how trust and/or estate assets have been invested. In this case, the beneficiary should obtain sufficient documentation to determine the identity of the entity in which an investment has been made, and the type and nature of investment, and whether the fiduciary (or perhaps a certain beneficiary) has a personal involvement or potential benefit from the investment that has not been clearly disclosed.

31 It is important to assess whether funds were improperly uninvested or placed in poorly performing instruments such as certificates of deposit or money market accounts. A beneficiary’s analysis may reveal that poorly invested funds could have yielded much more gain/income to the trust or estate from prudent investment management. Improper management is often subject to penalties in various states under Uniform Prudent Investment Acts.

32 A common technique is to compare investment performance with returns achieved on the Dow Jones or S&P 500 indices. If funds were invested in individual stocks, quotation information can be obtained to track the gain or loss in value and dividend performance to enable a comparison of the results of analysis with the accounting.

33 For example, if the investment should have yielded a higher return than disclosed, this could indicate that the fiduciary diverted gains or income have been diverted for his or he own benefit. The beneficiary must scrutinize source documentation to verify the claims in the accounting.

34 See Alford v. Marino, 14-04-00912-CV, 2005 WL 3310114, at *5 (Tex. App.—Houston [14th Dist.] Dec. 8, 2005, no pet.)(trial court correctly placed the burden on guardian to account for expenditures and rebut the presumption of unfairness with respect to numerous unaccounted for expenditures of the ward’s funds; the trial court could have determined that guardian benefitted personally from undocumented and unsupported expenditures

35 Frequently encountered issues in verifying and analyzing the reasonableness of expenditures include situations where the fiduciary expends excessive amounts of trust or estate funds on an otherwise legitimate expense or expends trust or estate funds for unjustifiable reasons.

36 This most commonly occurs when a fiduciary fails to sell an asset and incurs significant carrying costs for unreasonably long periods of time.

37 Frequently encountered issues in verifying and analyzing the validity and reasonableness of expenditures include situations where the fiduciary brazenly categorizes personal expenses as legitimate trust or estate expenses.

38 For example, problems can arise where an executor takes control (intentionally or inadvertently) of a non- probate asset and expends funds from same.

39 Eaton v. Husted, 141 Tex. 349, 357, 172 S.W.2d 493, 498 (1943).

40 Id.

41 For example, did the executor have the power to sell an asset and was it done for a proper purpose? See

e.g. Tex. Estates Code § 402.052. If a trustee had the discretion to sell, partition, or divide an asset, was the discretion exercised reasonably and impartially?

42 Common issues concerning include determining: whether the appraisal was recent or whether a new appraisal is warranted; whether the appraisal was prepared by a reputable source; whether there were any unusual assumptions, qualifications, or limitations on the opinion that would affect the stated value; whether an independent, third-party valuer was engaged to value assets for which no market quotation can be readily obtained; what length of time the property was on the market; how many offers were made; and whether fiduciary had any close affiliations or connections with the buyer.

43 Common issues include instances where values reported in the accounting include unwarranted discounts (e.g. to attempt to gain a more favorable share of a trust or estate for one beneficiary over others where the

trust or estate calls for equal distributions) or inflated values (e.g., to increase a commission), or even instances where the values in the accounting fail to report waste on the fiduciary’s watch.

44 Tex. Estates Code § 352.002; see also In re Rosenfield’s Estate, 371 S.W.2d 95 (Tex. Civ. App.—Dallas 1962, no writ).

45 Usually a will or trust provides for “reasonable compensation,” but in some instances, a specific method will be prescribed. In such instances, the beneficiary will need to verify that the compensation paid is consistent with the terms of the will or trust.

46 This can be important where it suspected the fiduciary has engaged in self-dealing or expended funds

improperly and attempts to camouflage or whitewash such activity as “compensation.”

47 This can be useful if commingling is suspected.

48 See e.g. Tex. Estates Code § 352.002.

Download the Full Publication

Find out more about Bryan Finley and Ryan Fraud and Forensic Recovery